|

In December 1914 Brigadier-General Trevor Ternan, CB, CMG, DSO was

recalled from retirement to command the new unit. At this time the

men were training, mainly in civilian clothes, in and around

Newcastle itself. The 1st and 2nd Battalions were in the city, the

3rd was at Newburn and the 4th at Gosforth. Drilling was carried out

in the streets of Newcastle, the men being mainly in civilian clothes

and carrying broom handles to represent rifles.

Officers for the New Army were obtained from a number of sources.

Some 500 officers from the Indian Army were home on leave, and these

were dispatched to various units more or less at random. The War

Office had drawn up a list of 2,000 young men, most of whom had

recently left university or public school, as being suitable junior

officers, and invitations to volunteer for commissions were sent to

these. This still left a huge gap in the supply of officers, as each

new battalion needed over 30. The number was made up by bringing men

out of retirement, such as Brigadier-General Ternan. Some of these

men had seen active service as recently as the Boer Wars of 14 years

earlier, but others had been retired much longer. At least one such

officer had seen action in the Ashanti War of 1873.

The Tyneside Scottish Battalions were commanded at first by Lt-Col

C H Innes-Hopkins (1st Batt.); Col V M Stockley (2nd Batt.); Lt-Col A

P A Elphingstone (3rd Batt.); and Capt J C Campbell (4th Batt.). Over

the ensuing months some of the commanding officers changed, but

Lt-Col Elphingstone remained with the 3rd Battalion, and led it at

the Battle of the Somme.

The problems which now beset the newly formed Brigade were no

different to those being experienced all over the country.

Overwhelmed by the rush of volunteers, the Army was unable to cope.

Ex-Regular NCOs were recruited and formed the basis of the NCOs in the new unit. The Regimental Depot then turned to the War Office

with demands for advice, ration money, equipment and, above all,

instructors. The replies, when they came, generally consisted of

little more than terse orders to "Carry On".

Obviously, the present arrangements for billeting of the Tyneside

Scottish were far from satisfactory, and so it was decided to move

the Brigade to a hutted camp specially constructed in the Duke of

Northumberland's Park at Alnwick. Accordingly, on 29th January 1915

the 1st Battalion route marched from Newcastle, halting for the night

at Morpeth and arriving at Alnwick the following day. Brigade

Headquarters moved on 1st March, and the 2nd Battalion on the 12th

March. The remaining two Battalions followed a little later.

Meanwhile, the question of uniform was being addressed. At first,

the Battalions adopted a variety of tartans, but as some doubt was

expressed as to the legality of this, a new tartan was designed and

adopted by the whole Brigade. A cap badge was also designed, and this

incorporated both Scottish and Tyneside elements. The design had been

submitted by a junior officer of the 4th Battalion. The men of the

Brigade did not wear the kilt, but instead wore trews in the Brigade

Tartan. The headdress adopted was the Glengarry. In addition to the

Brigade uniform, every soldier was equipped with the basic

infantryman's kit, which amounted to about one third of his own

weight. Each Battalion was entitled by regulation to a small pipe

band, and these were equipped by the Tyneside Scottish Fund, each

uniform costing some £30. The pipers themselves had been

recruited on the basis of their musical skill, and some leeway was

allowed regarding age. Pipe-Sergeant Barton was well over 40, and had

three sons serving in the Brigade's pipe bands.

Recruits learning to handle rifles

At Alnwick the Brigade settled into the routine of serious

military training. The Park itself was used for drill, and there were

rifle ranges a few miles away. The moorland in the area later

provided ground in which trench digging could be practised, and also

area for attack and defence exercises. The men were taught to dig and

build the 'ideal' trench, six feet deep with parapets of sandbags to

absorb rifle bullets, fire steps for sentries, and duckboards over

drainage channels. At intervals along the trenches were dugout

shelters to afford some protection from the weather. Life was not all

work, as the men were also engaged in various sporting activities,

and were able to return home occasionally on weekend leave.

On 20th May 1915 the Brigade achieved official recognition when it

was inspected on Town Moor, Newcastle, by HM King George V,

accompanied by Lord Kitchener. The Brigade had been taken into the

city by train and several other Brigades were also on parade. All in

all the King inspected some 18,000 troops. As the unit was still not

fully kitted out, it was loaned some rifles which were said to have

come from the Tower of London. Whether that was true or not, as soon

as the parade was over they were collected in and dispatched

elsewhere. One result of this inspection was that His Majesty

suggested to Ternan that the Brigade exchange its Glengarries for

Balmorals, as these gave better shade to the eyes. Kitchener agreed

and told the Commanding Officer to send in the necessary request.

This Ternan did on the following day, but it was several months

before supplies eventually arrived.

In the following month the Tyneside Scottish was designated as the

102nd Brigade (having originally been the 123rd Infantry Brigade),

part of the 34th Division of the British Army. Their old friends and

rivals, the Tyneside Irish, were designated the 103rd Brigade, and

also attached to the 34th Division, commanded by Major-General C

Ingouville-Williams CB, who had started the War as a Brigadier.

James Austin Brown had, for some reason, resisted the earliest

rush to volunteer, and records show that he enlisted on 21st July

1915, probably as a result of the Brigade's final recruiting push to

replace unsuitable men before leaving Alnwick. He was 33 years old at

the time.

Training continued at Alnwick for a few more weeks, and then on

1st August the whole Brigade was moved south by rail to Ludgershall.

On the following day they were marched to Sandhill Camp, north east of Tidworth on Salisbury Plain. Two weeks later, on

15th August, responsibility for the unit was officially taken over by

the War Office, although the Tyneside Scottish Committee continued to

be active in supporting it in many ways.

Sandhill Camp was a tented camp, and the weather caused problems, strong

winds flattening tents on more than one occasion. During the stay at Ludgershall, training continued,

but partly because of condition at Sandhill, the Brigade

moved again on 26th September. This time their destination was Longbridge Deverill, a few miles south of Warminster. From now on the

Brigade appeared in the General Monthly returns of the Army, and

these give an idea of the unit's strength at this time. The 3rd

Tyneside Scottish (listed at 22nd Northumberland Fusiliers) had an

official establishment throughout its existence of 29 Officers, 6

Warrant Officers, 45 Sergeants and 937 Rank and File, giving a total

establishment of all ranks of 1017. In addition it was allocated 11

horses for Officers' use, and 52 horses and mules for "drivers,

riders and pack". Most of the monthly returns show the Battalion as

being over strength, for example in September 1915 it had a total of

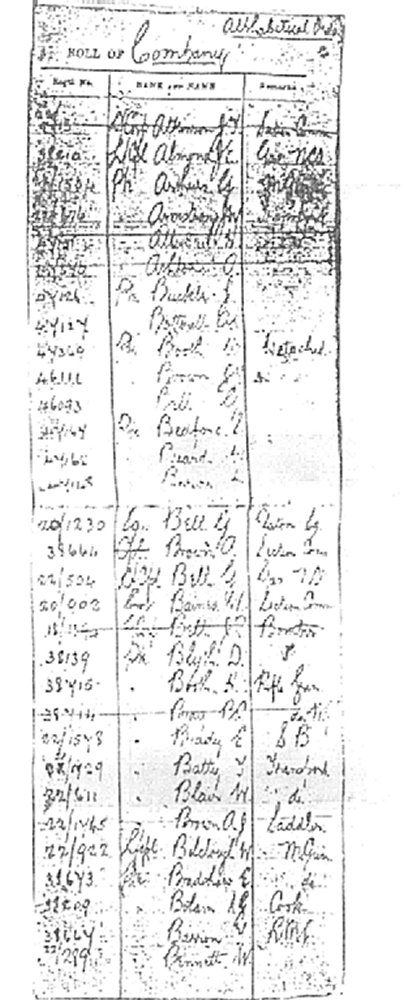

all ranks of 1122, and in the following month 1115. An alphabetical

list of an unidentified Company of the 3rd Tyneside Scottish shows

22/1745 Pte Brown as having the occupation of Saddler, no doubt as a

result of his civilian skills as a boot and shoe maker.

Time at Longbridge Deverill was spent in bringing the Tyneside

Scottish up to a peak of fitness and training, and General Ternan was

confident that the unit he commanded would perform well when it

finally went into battle. Amongst other changes to the organisation

of the Brigade, the number of Lewis guns was increased from two per

Battalion to one per Company. Weekly exercises were held, regardless

of the weather, which was often wet, and the Brigade gained a

foretaste of the conditions they were to find in France. Many of

these exercises were carried out at Sutton Veny, and entailed a six

mile round trip from camp to training area.

A Company list -

note 6th from bottom:

22/1765 Brown AJ

(sic) Saddler

At this time rumours were rife concerning overseas postings, and

for a time it looked as if Egypt was to be the destination, this

being taken as far as the issuing of tropical kit. Nothing came of

this, however, and in January 1916 the Brigade was ordered to France.

The men were given embarkation leave, and two Battalions were sent

back to Tyneside with pay and ration money for six days. On their

return the other two units were sent off, but they were only given

four days allowance. The men took matters into their own hands, and

four days later the special leave trains returned south with only a

handful of NCOs. After another two days nearly 2,000 men turned up on

Newcastle Central Station with no transport, but with plenty of

wives, children and girl friends to see them off. Despite the chaos,

they eventually made it back to camp at Warminster where the men were

paraded and given a firm dressing down, but only a few persistent

offenders seem to have received any punishment.

...

Chapter 3

...

Back to

Contents Page Back to

Contents Page

|